About the Martyrs

Nearly four hundred years has passed since St. Jean de Brébeuf and his companions laid down their lives for the Indigenous people and the faith. This notion of self-offering love and discovery forms the spirit of this site today, as it did in the beginning. We honour these martyred men at Martyrs' Shrine as well as the vision of community they had established back in the early 17th century.

On this page, you will learn about the origins of these Jesuit missionaries, the factors that led them to this site centuries ago, why we honour them today at Martyrs' Shrine, and how their actions has granted us a better understanding into the Indigenous community during this early contact period.

Who Are the Jesuits?

The Jesuits, officially known as the Society of Jesus, were founded by Ignatius Loyola, born in 1491. Ignatius was a Basque soldier who once believed that his destiny was to be found in material successes: to find a wealthy woman, to obtain an esteemed position in the royal court, and having honour and glory in the service of his kingdom on the battlefield.

Ignatius, during one of his battles, had a cannon ball strike him in his knee leaving him debilitated for many months. He was brought back to his castle in Loyola and while in recovery was given several books to read - all books on the lives of the saints and of the life of Christ. During this time as he read and reflected he began to realize that actually the king he wanted to serve was not the King of Spain, but Christ the King for he was the greater king. The wealthy lady that he sought to find wasn't a noble woman at court, but rather, Mary the mother of God; the symbol of purity and love. These realizations transformed his life and he decided to give up all that he had and began a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, desiring to preach to the Islamic world and devote his life to being around the holy sites where Christ himself had walked.

Portrait of St. Ignatius Loyola by Jacopino del Conte

Sharing the Word in New France

Huge leaps in scientific and cultural discovery were being made in Europe in the early 17th century which forced a race to expand kingdoms and trade into the lands across the Atlantic initiated by trailblazing explorers like Samuel de Champlain - the founder of New France.

A settlement (known today as Quebec City) was established along the shores of the St. Lawrence which made it easy for ships to come in and out to trade goods, but by 1615 Champlain would discover that it was difficult to establish trade and industry in the interior. Infighting between indigenous groups and other Europeans created a turbulent environment, foreign language and foreign customs also disrupted relations. The interior required a more consistent and permanent approach - the establishment of communities - enter missionaries.

Since the earliest times of the Catholic Church, Christians have been spreading news of the Gospel to people all around the world. The reasoning for this was quite simple: when you love someone, you want others to know about them so that they can love them as well. Those who travelled to spread the Word were known as missionaries and they played a key role in introducing the faith from Europe into the so called "New World," as well as building the bridges necessary for kingdoms to develop industry.

Missionaries, particularly the Jesuit missionaries, viewed the lands of the New World as a mystical landscape where human souls longed, in a profound way, to come to know God never having heard the name before. When they were invited to establish a new settlement in the interior, it was a welcome opportunity for them to fulfil their mission. The missionaries chose to leave the centers of intellectual discourse in Europe to lead a harrowing life overseas learning from and sharing experiences with the Indigenous peoples. The missionaries were known to be highly adaptable when faced with new and differing cultures, which was certainly a challenge faced by the likes of Jean de Brébeuf and his companions when they arrived in New France.

Seventy-one years after the approval of the Jesuit Order by Pope Paul III in 1540, and fifty-five years after the death of its founder, St. Ignatius Loyola, the first Jesuit set foot in what is now Canada, at Port Royal on May 22, 1611. Immediately upon stepping off the ships from France, they began discourse with the indigenous people. They would eventually accompany ally Indigenous guides into the untamed early Canadian wilderness.

'Fragile Trust' by Robert Griffing

'Jesuit missionary and Indians' by Wilhelm Lamprecht

The Wendat (Huron) Mission

Although several missions were created throughout the 17th century in New France by several religious orders, none quite resonated throughout time as did the mission to the Wendat People, aptly named Sainte-Marie after Mary, the mother of God; the human embodiment of purity and love. Champlain initially encouraged the Recollect Fathers to set up a community in Wendake, deep into the Canadian interior. They were the first religious group working to improve the understanding of the various Indigenous people living there. Unfortunately they were unsuccessful in their mission and were later replaced by French Jesuits in 1625.

Jean de Brébeuf was assigned to the position of Jesuit Superior the following year and began work on assessing the local languages and developing a dictionary to assist his fellow priests in communicating with the local people. The Jesuit missionaries continued to study the local languages and customs and genuinely participate and live among the Wendat people. The mission was centrally located in Wendake, which became the heart of the Wendat-Christian community. It was connected to various trading posts and centrally located from native villages and with navigable routes across the Great Lakes and to Quebec City, the economic hub of New France.

The Wendat people were viewed by the missionaries as people of great courage and strength. They had so much in their lives, yet not Christ. In the hearts of the missionaries, they wanted to share the experience of Christ with the native peoples, and were successful in doing so for 16 years, at which time the Wendat Confederacy was destroyed and displaced by the Iroquois along with the deaths of Brébeuf and his companions.

During its operation, the mission served as a headquarters and retreat for Jesuits in the area in the heart of the Wendat-Christian community - a space set apart from native villages that missionaries could visit seasonally to re-root themselves to the faith before they would head out again into the various villages to live among the Indigenous people. Sainte-Marie was a home of peace; a safe space to engage in prayer and discovery. This was a melting pot community of indigenous and European cultures; a human community based on willing openness to all, on an ideal of sharing and service. From here, missionaries and the Indigenous people engaged in studied on a range of topics including anthropology, cosmology, astronomy, theology, botany, linguistics, philosophy and cartography. It was a place of scholarship and intellectual conversation between Europeans and Indigenous people. Sainte-Marie became the second largest settlement in New France outside of Quebec City and Ontario's first European community, which made it an attractive target for Iroquoian attack.

Indigenous people did not live at the mission full time, but two longhouses were built in the traditional native style to accommodate those who wished to stay for periods of time. Visitors were welcome and the mission had a sort of open-door policy whereby native peoples could open conversations with the Europeans, participate in rituals and practices, or to learn the spiritual and European customs of their new neighbours. The idea behind this was to allow native persons an opportunity to have an immersive experience into the life of an established Christian community, which was not available to them in their native villages.

The construction of the fortified Sainte-Marie mission we see recreated today at Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons began in 1639 by invitation of several local chieftains. Brébeuf finished his time as Superior and was succeeded by Lalemant, who reimagined a fortified mission residence - a space that would help ward off the Iroquoians. Within it's palisade lie an economically self-sufficient site, containing a barracks, church, workshops, residences and a sheltered area for Indigenous visitors. The mission was intended to be a seminary for Jesuits and Indigenous people to cohabitate and be formed for a life of faith.

In 1648 and 1649, the Iroquois began a series of devastating attacks on local Wendat and Petun villages including the Wendake mission which resulted in the deaths of Antoine Daniel, Jean de Brébeuf, Gabriel Lalemant, Charles Garnier and Noël Chabanel who were all later canonized. Wendake was showered in martyrs' blood during these years, along with the blood of many Indigenous peoples who bravely adopted the faith.

In the Spring of 1649, the mission was burned to the ground by its residents to protect it from desecration from the hands of the Iroquois invaders. The mission of Sainte-Marie was re-established briefly on Christian Island among the Beasoliel First Nation, but was relocated to Quebec after one year due to continued Iroquois interference and a disasterous winter famine. The residents revisited Sainte-Marie and exhumed the bones of Brébeuf and Lalemant, removed the flesh, and took the bones with them to Quebec City to be kept as relics for they knew in their hearts that one day, these men would be declared saints.

It was Fr. Paul Ragueneau who led the retreat back to Quebec from Christian Island, and was responsible in 1652 for beginning the process that eventually led to the canonization of Brébeuf and his companions.

The Canadian Martyrs

The martyrs which we honour today at Martyrs' Shrine (also known as the North American Martyrs) were Jesuit missionaries who had left their comfortable lives in France to work among the Indigenous people who occupied the territory of Wendat Nation which we know today as Georgian Bay.

It was at St. Peter's Basilica in Rome on July 21, 1925 when Pope Pius XI, crowned in full regalia, finally rendered homage to these men, the Canadian Martyrs, in the form of beatification. 40,000 faithful appeared in Rome and 6,000 showed up in the fields around Sainte-Marie to attend the site's inaugural liturgy under the watch of the Provincial Jesuit Superior, Father John Filion who led the build of the Martyrs' Shrine next to the Ste. Marie site.

It was on June 29, 1930 that the French Jesuit men who gave their lives to the faith and to the Indigenous people who they had come to serve, were finally canonized - some 278 years after Father Paul Ragueneau first began the process.

Early Indigenous-European Relations

At various periods of time, humans had entered the lands of North America from the Eurasian and African continents, whether by boat or ice bridge. There is an estimated 23,000 years of human history in North America. As climate changed throughout the millennia and glaciers receded, it exposed fertile lands and waterways; areas suitable for hunting, fishing, gathering and later, agriculture. Early human tribes settled in and around these sites as they provided resources for food, protection, new technologies and trade.

The arrival of early modern Europeans to North America occurred as early at 950AD with vikings, later the Basques and other European nations. The land was viewed as an untapped space of resources, from fishing, pelts and furs, metals and timber, and a place suited for colonization. At the same time, as Europeans discovered that people already resided there, it sparked profound philosophical and theological questions around, "How did these people get here?" and, "Are they like us?" For the Christian community back in Europe, and for the missionaries in the New World, they had the Bible as their tool and could only look to scripture to understand these types of questions.

The Indigenous communities, who were once seen as outliers who were barbaric and vain, were quickly understood to be far more closely related to Europeans. Although the Indigenous communities lacked the large cities of Europe, they had established governments, traditions, trade networks and technologies that allowed them to master their environment in the Canadian wilderness.

Preserving and Protecting History

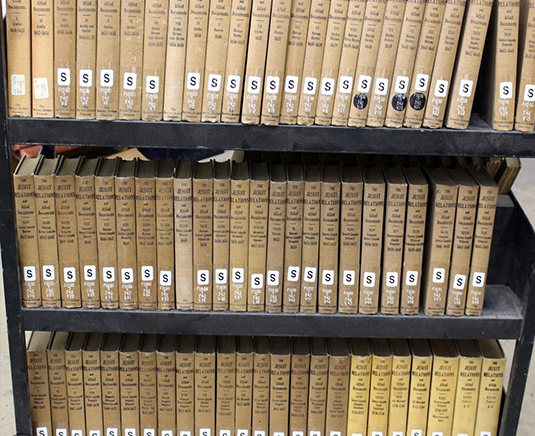

Much of the early Indigenous history was passed down orally which has unfortunately made it difficult to understand the complexity of the cultures during and after the colonial period in which the Jesuit missionaries entered these lands. The sad reality of subsequent death, dispersal and disease that followed this early-contact period negatively affected how those oral narratives survived. The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents of the 17th century, written largely by the missionaries, are one of the few surviving sources of information serving to help Indigenous people preserve and protect their own history. These letters form the basis of our modern understanding of the practical and pious experiences that early Jesuit missionaries had – as well as their interaction with the Indigenous peoples of the time – and how their religious worldview shaped that often complex, turbulent, faith-filled, and loving experience.

The Jesuits of Canada and the ministry at Martyrs' Shrine are proud guardians of this early history, that form some of the foundation stories of our modern nation. Work continues on developing a deeper understanding of the early relationship with missionaries, the Indigenous people, and the community that they shared.

Native American Pow Wow Performance

Catalogue of Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents

"My God and my savior Jesus, what return can I make to you for all the benefits you have conferred on me? I make a vow to you never to fail, on my side, in the grace of martyrdom, if by your infinite mercy you offer it to me some day." - Jean de Brébeuf